As FIFA Women’s World Cup takes over the world, SALIFE meets football pioneer Moya Dodd AO whose determination took her from a Port Adelaide soccer field to vice-captain of the Matildas and then on to the board of the world’s most powerful sporting organisation.

Game changer

Who is Australia’s most famous football player? Ask anyone on the street and they’re likely to give the same answer: Sam Kerr. Her stardom transcends code and gender. And yet, Kerr’s success would have been unimaginable last century when, for decades, women’s football was discouraged around the world.

The women’s game had begun to flourish in many countries after World War I but the momentum was short-lived when the English Football Association requested that clubs refuse use of their grounds to women’s matches. The association stated: “the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged”.

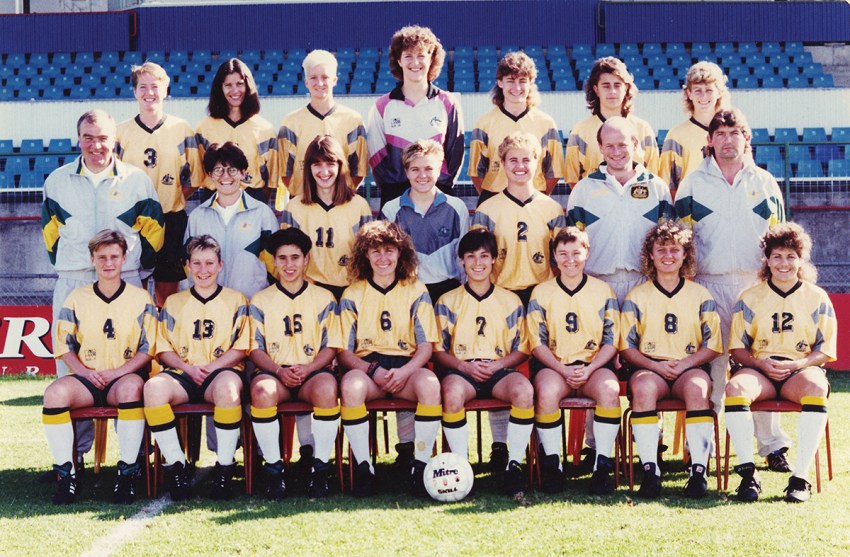

But in June 1988 – 35 years ago this month – a team of Australian players stepped onto a football pitch in China to play a historic game and prove an almighty point for women’s football.

The 1988 Women’s Invitation Tournament was a test-run for the first ever Women’s World Cup. The first game pitted Australia against Brazil and, incredibly, the Aussies downed the football giants 1-0.

Adelaide’s Moya Dodd was an up-and-coming rookie on the history-making team, none of whom were paid to play. “I think we surprised a few people, including ourselves; it was a miracle,” says Moya, who was a 23-year-old University of Adelaide law student at the time.

“I came on as a substitute towards the end of the game. Here I was, 1-0 up against Brazil in the heat of a southern Chinese summer, desperate to ensure that we didn’t concede.”

The 1988 tournament paved the way for the first Women’s World Cup in ’91. The Matildas name was coined for the next Cup in ’95, which Moya missed because of a torn anterior cruciate ligament in her knee.

She represented the Matildas for almost a decade, including as vice-captain; a feat even more remarkable considering she had only started playing at the age of 13 but was playing for the green and gold by the age of 21.

Moya’s journey began as a youngster kicking the footy – the Aussie Rules kind – at primary school in Adelaide’s west. “I would have a mad 15 minutes every day, tearing around playing footy with the boys at recess time,” says Moya.

Moya’s father Jeff Dodd was a fireman and their family lived at the Woodville Fire Station. At age 10, Moya’s parents moved the family out of the station and into a “proper house” at Semaphore Park.

“It had a lawn and a wall that I could kick against, so that was a plus, and we finally got a television. Each week, there was an hour of English football on TV and I would watch it religiously. I followed Liverpool and I would read the papers every day for football news,” she says.

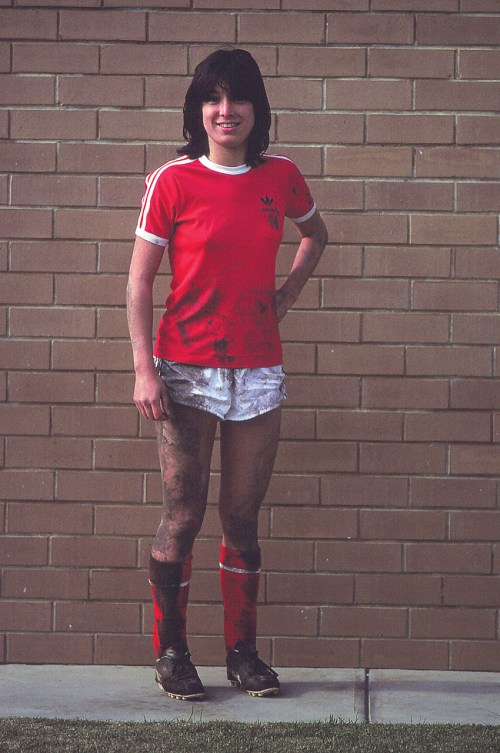

Moya was reading the newspaper one day when she discovered in very fine print scores for a local women’s soccer league. “I thought, ‘oh my God, I could play in a proper team!’ One of the teams was Port Adelaide,” says Moya.

On school nights, Moya would ride her bike to trainings with Port Adelaide Soccer Club’s senior women’s side. “That became the centrepiece of my life from the age of 13 onwards. Looking back, I do wish I’d been able to start much younger, but there was no underage girls’ football at the time,” she says.

“In my first season I was playing against Diana Hall, who was a national team player, and I remember riding my bike to the field thinking, ‘I’m going to play against an Australian player today’. I was excited that we were going to measure ourselves against someone at that level.

“I think we got walloped, but I remember riding home, thinking, ‘that’s what the top level looks like and I’m going to have to work harder if I want to improve’.”

Moya continued to improve, and she was soon representing South Australia and then Australia.

“Whenever the Australian team got together to train or play, they were pretty intense times where you wanted to absolutely make the most of it,” says Moya. “It was a chance to forget about your job or your studies and just act like a full-time professional football player for a week or two.”

While studying law, Moya had a part-time job reshelving books in the University of Adelaide’s Barr Smith Library just to save money to play. “I remember getting a second part-time job at one stage because I needed to save up 700 bucks to go to the Australian Institute of Sport for a week-long training camp.”

On one occasion, Moya was flying with the Australian team to play in New Zealand, when the team’s order of tracksuits arrived late, directly to the airport, and players quickly traded sizes with each other and each sewed on their own coat-of-arms.

“I’m sure every single one of those players in the pioneering era has suffered financial disadvantage over their lifetimes because they didn’t get established financially when they were young,” says Moya.

“Nobody would exchange it for the experience, but it does explain why some people were not able to stay in the game for as long as they could have despite their ability and fitness; they simply couldn’t afford to.

“It’s so heartening to see now that players are remunerated for being in the national team and that we have a more professionalised league structure here in Australia. To have a daily training environment where you’ve got the support of top coaches, top medical staff, dieticians and psychologists, all those things go into making a great athlete.”

Since hanging up the boots with the Matildas, Moya has worked to champion women in sport. In 2013, she became one of the first three women appointed to the FIFA board. It was an exciting time to join, given the FBI was investigating FIFA members for corruption.

In 2015, Moya was in a Zurich hotel when the FBI raided hotel rooms to arrest several then-officials who were at the centre of the allegations. “There were some bad actors within the organisation and FIFA itself needed to prove that it was not a corrupt organisation. As part of that, it had to reform substantially,” she says.

In 2015, as the “FIFA-gate” scandal unfolded, Moya was among a team of people who lobbied for better inclusion of women in decision-making processes and larger investment in the women’s game. FIFA partially adopted the gender reform proposal, with a requirement that every continent must have a seat filled by a woman.

“I was glad to be there at that time because I could see that issues of gender balance within FIFA were quite acute. This was an organisation that for 108 years had a board comprised entirely of men. During that time, it had neglected women’s football quite outrageously and for such egregious reasons – or no reason, in fact.”

In 2016 the Australian Financial Review named Moya the most influential woman in Australia and in 2018 she was named the seventh most powerful woman in international sport (outside the United States) by Forbes magazine.

Today she lives in Sydney where she is a partner at law firm Gilbert + Tobin. Last month she was appointed as an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in the King’s Birthday Honours List for distinguished service to football as a player and administrator, as a role model to women, and to the law.

Moya also played a role with the Football Australia Bid Committee to secure the 2023 Women’s World Cup for Australia and New Zealand.

“There is a huge amount of work that gets done behind the scenes in any bid and I played a small part in all of that,” she says.

Now, the 2023 Women’s World Cup and its superstars like Sam Kerr will give young Australians the opportunity to experience professional football up close.

“Gender stereotypes are just so limiting not just for girls, but for all genders and playing sport is a good way to break free of that,” says Moya. “To be put down or derided because of sport – I experienced that from time to time as a kid, and I think a lot of girls still do. What’s it to you if I want to kick a ball?

“It is important that these role models who are breaking stereotypes are given their place in the sun and the media coverage and respect they deserve. These things make a difference.”

Moya will return to her hometown of Adelaide to watch the blockbuster China versus England game on August 1.

“I wouldn’t miss it. I think Hindmarsh Stadium is the best ground in Australia to watch football; it’s just so exciting,” she says.

Moya continues to play football in an over-40s competition but would love to wind back the clock if she could. “Would I love to be playing now? Of course. You’d always like to lose a few decades and do it all again, especially with the opportunities that exist now,” she says.

“I hope the game’s pioneers can feel proud that what they started has gone on to become the game you see today. I hope they can recognise themselves in that.

“I’m proud to have been a part of it.”

Adelaide’s FIFA 2023 Women’s World Cup matches kick off at Hindmarsh Stadium on July 24 with Brazil versus Panama.

This article first appeared in the July 2023 issue of SALIFE magazine.

including free delivery to your door.